Merchant Vessel Carrying 6,500 Kilos Of Cocaine Intercepted Off Canary Islands

October 27, 2025

Engine Room Fire Leaves Car Carrier Drifting Without Power In The English Channel

October 28, 2025

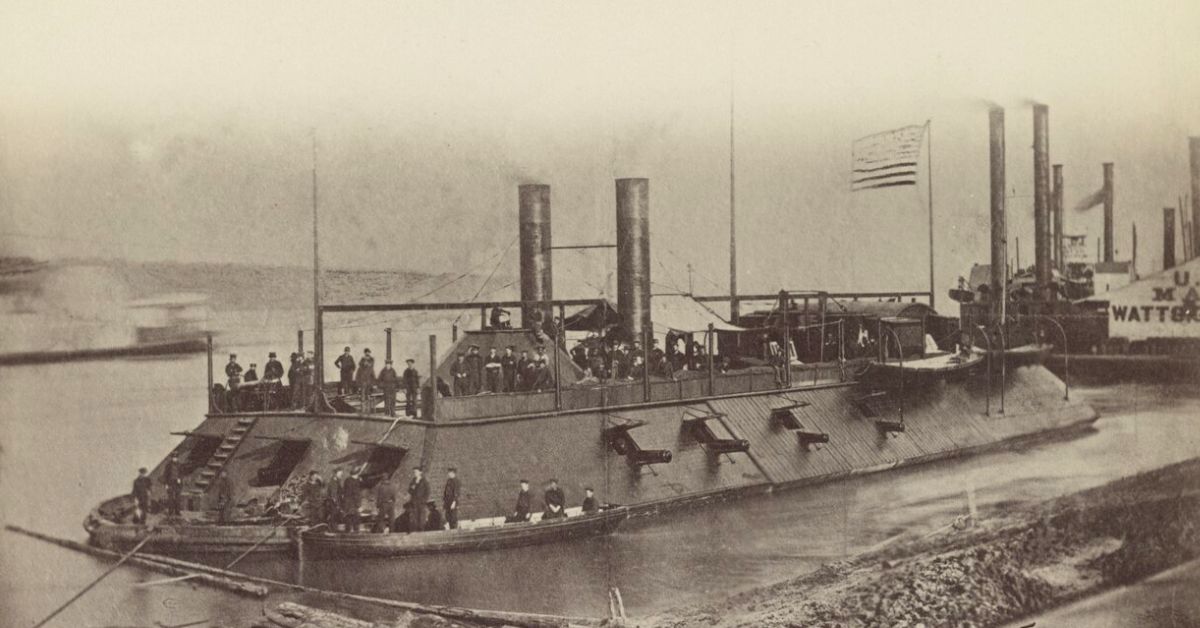

Researchers at the University of Minnesota have discovered extensive fungal decay in the USS Cairo, one of the first ironclad and steam-powered gunboats used during the United States Civil War.

The findings have raised concerns about the long-term preservation of the historic vessel, which has been on public display for decades.

The study, recently published in the Journal of Fungi, highlights how a diverse range of fungi continues to degrade the ship’s wooden structure despite earlier conservation treatments.

The research forms part of ongoing efforts to understand how microorganisms contribute to the deterioration of historic wooden artefacts.

Built in 1861, the USS Cairo sank in December 1862 after striking a torpedo in the Yazoo River. The vessel was recovered nearly a century later and has since been displayed at the Vicksburg National Military Park in Mississippi.

Although the ship is protected by a canopy, it remains exposed to humidity and other environmental factors that accelerate microbial degradation.

According to lead researcher Professor Robert Blanchette from the university’s College of Food, Agricultural and Natural Resource Sciences, the continued degradation of the ship has become a significant concern for conservators. He noted that understanding the microorganisms responsible for the decay is essential to determining the right preservation approach.

In collaboration with conservators Claudia Chemello and Paul Mardikian from Terra Mare Conservation and the U.S. National Park Service, the research team examined the ship’s timbers to assess the extent of damage. They analysed the chemical composition of the wood, studied the decay patterns, and identified numerous fungal species living within the structure.

The study found that many areas of the ship showed advanced stages of decay. Although earlier wood preservation treatments had been applied, certain fungi appeared tolerant to these chemical compounds and continued to colonise the timbers over time.

The researchers identified both soft rot and white rot fungi throughout the vessel, many of which seemed capable of surviving even in treated wood.

The team observed that wood exposed to outdoor environmental conditions for long periods is highly susceptible to microbial damage. Even preserved wood can become a habitat for fungi that adapt to resistant materials, allowing them to cause further degradation.

To prevent further damage, the researchers recommended placing the vessel in a controlled environment to reduce moisture and exposure to natural elements. They said a new protective structure could help slow or stop the decay caused by fungi resistant to preservation treatments.

The study also called for further research into the biology and ecology of these fungi to better understand their interactions with wooden artefacts and develop improved methods for controlling them.

The study was supported by the USDA Hatch Project and the U.S. National Park Service.

Reference: University of Minnesota

Source: Maritime Shipping News